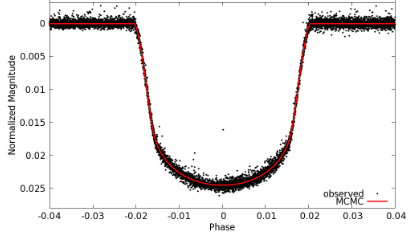

If, during a transit of its star, an exoplanet crosses a star spot, it will be covering a region that is dimmer than the rest of the star. Since less light will be being occulted, we will see a small increase or “bump” in the transit profile. WASP-85 was recently observed by the K2 mission, getting sufficiently high-quality photometry that it could reveal such starspot `bumps”.

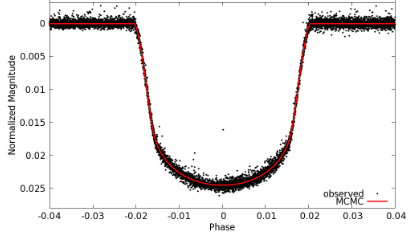

Here is the transit proflle, from a paper by Teo Močnik et al, which contains all the K2 data folded in:

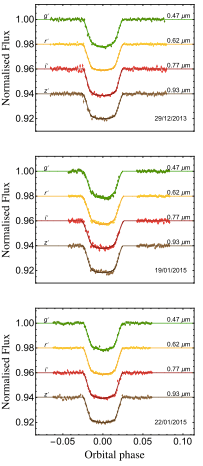

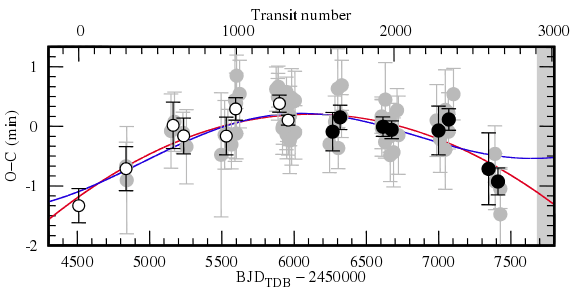

Teo Močnik then subtracted the overall transit profile, thus showing the departures from the average behaviour, and produced a plot of each transit:

The vertical dashed lines show the regions in transit. The lightcurve bumps circled in red are starspots being occulted. (Blue arrows are times when K2 fired its thrusters, which can cause a feature in the lightcurve.)

The interesting question is whether a bump recurs in the next transit, but shifted later in phase, as it would if the same starspot is being occulted again. This would happen if the planet’s orbit is aligned with the stellar rotation. In that case, as the star rotates, the spot moves along the line of transit, to be occulted again next transit.

An illustration of a planet occulting a star spot when the planet’s orbit and the star’s rotation are aligned. Graphic by Cristina Sanchis Ojeda

To judge whether the starspot bumps repeat, Teo gave all the co-authors a set of lightcurves and asked them to judge which features in the lightcurve were genuine bumps. But, to avoid human bias, he first scrambled the order of the lightcurves, so that the co-authors didn’t know which lightcurve came next.

The result is that we think that starspots do repeat, shown by the red linking lines in the above figure. This shows that the planet’s orbit is aligned, and it also allows us to estimate the rotational period of the star.