As NASA’s Kepler mission covers fields in the ecliptic previously surveyed by WASP, it is obtaining photometry of unprecedented quality on some WASP planets. The big news this week is the discovery of two more transiting planets in the WASP-47 system.

WASP-47 had seemed to be a relatively routine hot-Jupiter system with the discovery of a Jupiter-sized planet in a 4-day orbit, reported in a batch of transiting planets from WASP-South by Hellier et al 2012.

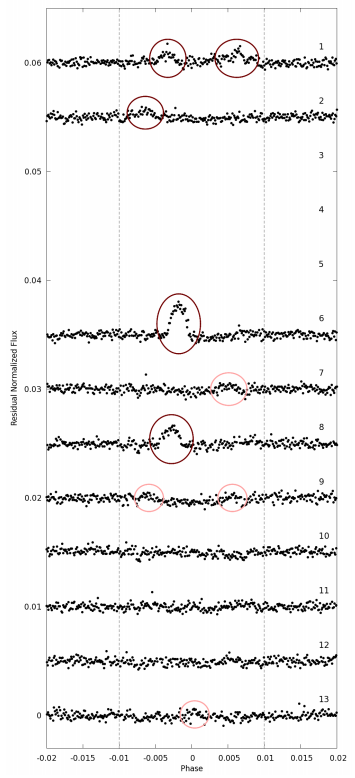

But WASP-47 is anything but routine. Now Becker et al have announced that the Kepler K2 lightcurves show two more transiting planets: a super-Earth planet in an orbit of only 0.79 days, and a Neptune-sized planet in an orbit of 9.0 days. Being much smaller, these planets cause transits that are too shallow to have been seen in the original WASP data.

The super-Earth, labelled WASP-47c, has a radius of 1.8 Earths while the Neptune, labelled WASP-47d, has a radius of 3.6 Earths. The triple-planet system is dynamically stable, but the gravitational interaction causes perturbations in the orbits, leading to variations in the times of the transits.

Such “transit-timing variations” or TTVs lead to estimates of the planetary masses. Becker et al find that the hot Jupiter has a mass of 340 Earths (consistent with the mass of 360 Earths originally reported by Hellier et al from radial-velocity measurements), while the Neptune has a mass of 9 Earths. The super-Earth must be less massive than that, but current timing measurements are not sensitive enough to say more.

As if three planets were not enough, there is a probable fourth planet orbiting WASP-47. The Geneva Observatory group routinely monitor known WASP systems, taking radial-velocity measurements over years, to look for longer-period planets. Marion Neveu-VanMalle and colleagues have recently reported the detection of another Jupiter-mass planet orbiting WASP-47, this time in a much wider orbit of 571 days.

The WASP-47 system has now become hugely interesting for understanding exoplanets, and will trigger many additional observations of the system. For example, being bright enough to allow good radial-velocity data, it will provide a much-needed check that the mass estimates from TTVs match those from the more traditional radial-velocity technique.

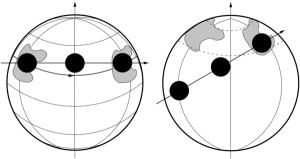

The system will also be of strong interest to theorists, who will want to understand the formation and origin of a planetary system with this architecture. One immediate consequence is that it shows that a hot Jupiter can arise by inward migration through the proto-planetary disk, without destroying all other planets in its path.