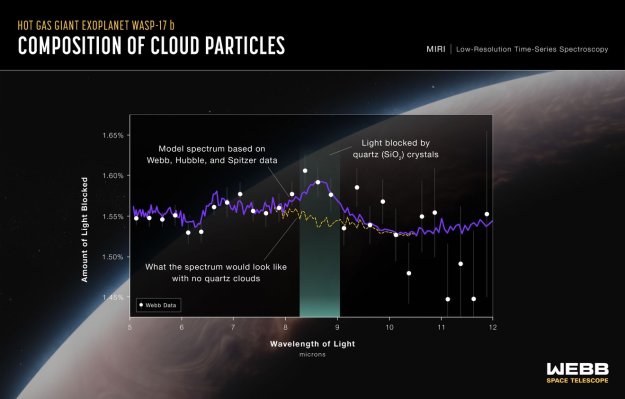

NASA has put out a press release about observations of WASP-43b with the James Webb Space Telescope. The paper in Nature Astronomy, led by Taylor Bell, reports observations around the orbit with the MIRI instrument.

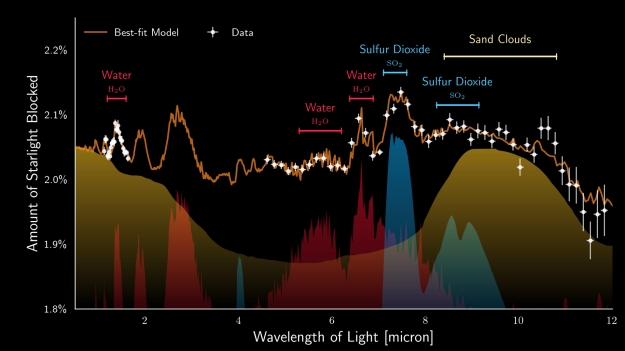

JWST/MIRI phase curve of WASP-43b (Image Credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, Ralf Crawford (STScI)).

“An international team of researchers has successfully used NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope to map the weather on the hot gas-giant exoplanet WASP-43 b.

“Precise brightness measurements over a broad spectrum of mid-infrared light, combined with 3D climate models and previous observations from other telescopes, suggest the presence of thick, high clouds covering the nightside, clear skies on the dayside, and equatorial winds upwards of 5,000 miles per hour mixing atmospheric gases around the planet.

“The investigation is just the latest demonstration of the exoplanet science now possible with Webb’s extraordinary ability to measure temperature variations and detect atmospheric gases trillions of miles away.”

The visibility of the heated face of the planet varies around the orbit, producing the above “phase curve” variation. (Image Credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, Ralf Crawford (STScI))