Press Release: Scientists have detected an exoplanet atmosphere that is free of clouds, marking a pivotal breakthrough in the quest for greater understanding of the planets beyond our solar system. (Link to Nature paper)

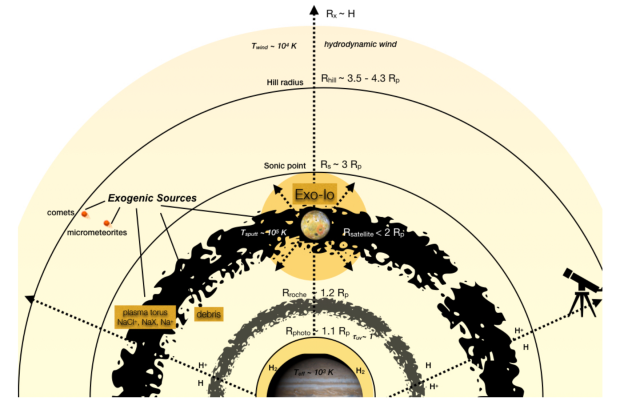

Figure 1 | Exoplanets in orbits close to the line of sight for us on Earth periodically pass in front (transit) and behind (secondary eclipse) of their host stars. Transits and eclipses are a powerful indirect way to study the composition of exoplanet atmospheres. Image credit: N. Nikolov

An international team of astronomers, led by Dr Nikolay Nikolov from the University of Exeter, have found that the atmosphere of the ‘hot Saturn’ WASP-96b is cloud-free. Using Europe’s 8.2m Very Large Telescope in Chile, the team studied the atmosphere of WASP-96b when the planet passed in front of (“transited”) its host-star (Figure 1). This enabled the team to see the starlight shining through the planet’s atmosphere, and so determine its composition.

Just as an individual’s fingerprints are unique, atoms and molecules have a unique spectral characteristic that can be used to detect their presence in celestial objects. The spectrum of WASP-96b shows the complete fingerprint of sodium, which can only be observed for an atmosphere free of clouds (Figure 2). The result appears today in the prestigious research journal Nature.

Figure 2 | Sodium fingerprint in an exoplanet spectrum. Shown is the absorption due to sodium at each wavelength. More absorption means that we are looking higher up in the atmosphere, and the vertical axis therefore a measure of altitude in the atmosphere of the planet. An atmosphere free of clouds produces an intact sodium fingerprint (left panel). A cloud deck blocks part of the sodium in the atmosphere, partially removing its spectral signature (right panel). Image credit: N. Nikolov/E. de Mooij

“We’ve been looking at over twenty exoplanet transit spectra. WASP-96b is the only exoplanet that appears to be entirely cloud-free and shows such a clear sodium signature, making the planet a benchmark for characterization”, explains lead investigator Nikolay Nikolov from the University of Exeter in the United Kingdom.

WASP-96b was discovered recently by a Keele University team led by Professor Coel Hellier. It is the 96th planet announced by the Wide Angle Search for Planets. WASP-96b is a gas giant similar to Saturn in mass and exceeding the size of Jupiter by 20%. The planet periodically transits a sun-like star 980 light years away in the southern constellation Phoenix.

It has long been predicted that sodium exists in the atmospheres of hot gas-giant exoplanets, and in a cloud-free atmosphere it would produce spectra that are similar in shape to the profile of a camping tent.

“Until now, sodium was revealed either as a very narrow peak or found to be completely missing”, continues Nikolay Nikolov. “This is because the characteristic ‘tent-shaped’ profile can only be produced deep in the atmosphere of the planet and for most planets clouds appear to get in the way”.

“It is difficult to predict which of these hot atmospheres will have thick clouds. By seeing the full range of possible atmospheres, from very cloudy to nearly cloud-free like WASP-96b, we’ll gain a better understanding of what these clouds are made of”, explains Prof. Jonathan J. Fortney, study co-author, based at the Other Worlds Laboratory (OWL) at the University of California, Santa Cruz (UCSC).

The sodium signature seen in WASP-96b suggests an atmosphere free of clouds (Figure 3). The observation allowed the team to measure how abundant sodium is in the atmosphere of the planet, finding levels similar to those found in our own Solar System.

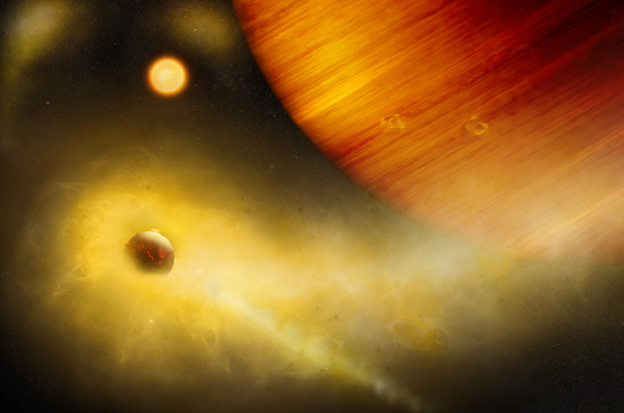

Figure 3 | An artist rendition of ‘hot Saturn’ WASP-96b. A distant observer would see WASP-96b blueish in colour, because sodium would absorb the yellow-orange light from the planet’s full spectrum. Image credit: Engine House

“WASP-96b will also provide us with a unique opportunity to determine the abundances of other molecules, such as water, carbon monoxide and carbon dioxide with future observations “, adds co-author Ernst de Mooij from Dublin City University.

Sodium is the seventh most common element in the Universe. On Earth, sodium compounds such as salt give sea water its salty taste and give the white colour of salt pans in deserts. In animal life, sodium is known to regulate heart activity and metabolism. Sodium is also used in technology, e.g. in the sodium-vapour street lights, where it produces yellow-orange light.

The team aims to look at the signature of other atmospheric species, such as water, carbon monoxide and carbon dioxide with the Hubble and James Webb Space Telescopes as well as telescopes on the ground.

Update: The story has been covered on over 50 websites, including Newsweek, Astronomy Magazine, the International Business Times, the Irish Times and others.