Most hot Jupiters are lonely planets. If they have companions, they are far out in distant orbits. Thus it was a surprise when a K2 lightcurve of WASP-47 detected transits of two small, rocky planets, one orbiting inside the hot Jupiter WASP-47b, and the other orbiting just outside (Becker etal 2015).

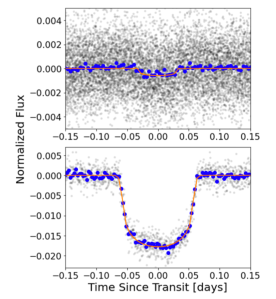

TESS light-curves showing transits of hot-Jupiter WASP-132b (bottom) and the newly discovered inner planet, WASP-132c (top).

Now a new paper led by Ben Hord reports a small companion planet to hot-Jupiter WASP-132b. Discovered in TESS light-curves and dubbed WASP-132c, this planet has an orbital period of 1 day and a size just below two Earth radii.

This is only the fourth hot-Jupiter system found to have small companion planets.

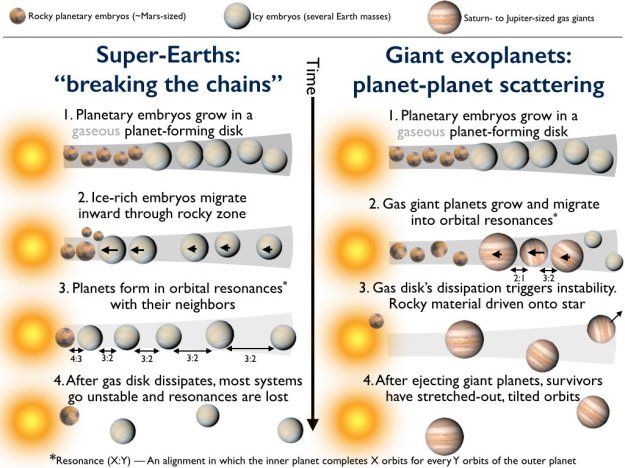

Schematics of the four known systems where a hot Jupiter has a rocky planet as a close companion. (From Hord et al, note that the diagram is not to scale.)

As explained by Hord et al: “The existence of a planetary companion near the hot Jupiter WASP-132 b makes the giant planet’s formation and evolution via high-eccentricity migration highly unlikely. Being one of just a handful of nearby planetary companions to hot Jupiters, WASP-132 c carries with it significant implications for the formation of the system and hot Jupiters as a population.”