WASP-107b is only twice the mass of Neptune but nearly the radius of Jupiter. It is thus a hugely bloated and fluffy exoplanet and one of the more important of the recent WASP discoveries, being a prime target for atmospheric characterisation (see the discovery paper by Anderson et al 2017).

WASP-107b was also in the Campaign-10 field of the K2 mission, leading to a Kepler-quality photometric lightcurve. Recent papers by two teams, led by Teo Močnik and Fei Dai, have arrived at a similar conclusion: WASP-107b seems to be in an oblique orbit, rather than in an orbit aligned with the rotation axis of the host star.

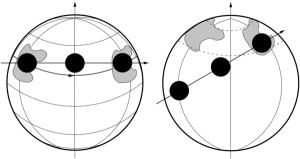

The conclusion comes from star spots. If the orbit is aligned, consecutive transits will repeatedly cross the same star spot, producing a “bump” in the lightcurve each time, whereas if the orbit is oblique this will not happen.

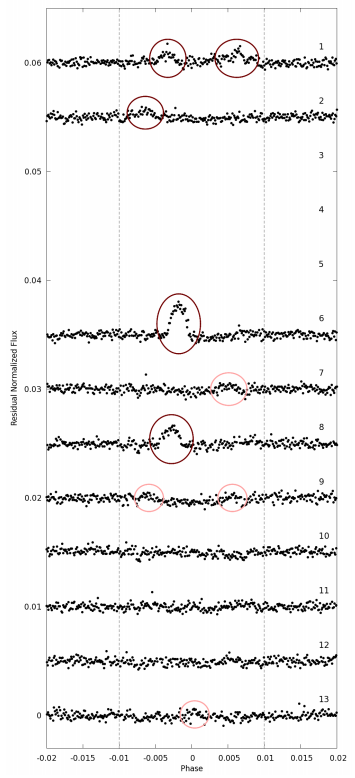

Thus one can play the game of looking for transit bumps and seeing if they repeat. But spots can change, by growing or shrinking, so is a smaller bump in the next transit the same spot, or a different one? Also, if there is some uncertainty in the rotational period of the star, then we’re not fully sure exactly where in the next transit the spot will recur.

In the figure at left (in which the transit itself, between the dashed lines, has been removed, leaving only the starspot bumps), obvious spots are circled in red, while possible spots are marked with a lighter red. The rotational period of the star is nearly three times the orbital period of the planet, and so, if the spots recurred, they would be seen every three transits. (The gap, and thus the missing of transits 3, 4 and 5, arose from a spacecraft malfunction.)

The conclusion is that the star spots do not seem to recur and thus that WASP-107b is in an oblique orbit.