The first extrasolar planet around a normal star was found in 1995. The first transit of an exoplanet across its star was detected in 1999. Astronomers worldwide realised that searching for transits would be an excellent way of detecting exoplanets. This would need wide-field surveys, building up lightcurves of millions of stars, since only a small fraction of stars were thought to host planets in tight enough orbits to produce the possibility of frequently recurring transits, and only the edge-on systems would actually show transits.

Don Pollacco, then at Queen’s University Belfast, had been developing “Comet Cams”, combining wide-field camera lenses with cryogenically cooled CCDs, primarily to study comets such as Hyakutake and Hale-Bopp. He realised that such hardware could find planet transits.

The WASP project (Wide Angle Search for Planets) began in 1999 as a collaboration between Queen’s University and the University of St. Andrews. Don Pollacco built a WASP0 prototype camera which was mounted “piggy-back” style on a commercial Celestron equatorial mount. Observations were made from the Canary Island of La Palma during the summer of 2000.

This instrument consisted of an Apogee 10, 14-bit 2kx2k CCD and a 6.3cm, F/2.8 lens, which gave it a field of view 9 degrees on a side. The first pipeline for data reduction was developed by Andrew Collier-Cameron at St Andrews. The 2000 season observations concentrated on two fields: the head of Draco and a field centred on the one known transiting planet, HD 209458b: detections of this transit by WASP0 proved that the method would work.

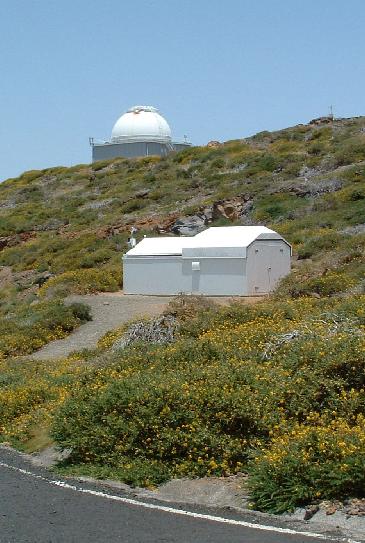

That year Pollacco widened the collaboration to include Cambridge University and Leicester University, and obtained a PPARC grant to build the first WASP system, proposed as a single-camera “WASP 1”. He then persuaded Queen’s University with a vision of a “SuperWASP” system, four cameras in parallel, greatly enhancing the sky coverage and thus the planet catch. Obtaining QUB funding in 2002 to add to the PPARC funding he set about designing and constructing what would become “SuperWASP” sited at the La Palma Observatory, and thinking even bigger, he designed room for eight cameras.

Meanwhile St. Andrews University set about the task of building a pipeline to process the data, expected to be 2000 CCD images per clear night, amounting to 40 GB. At Leicester, Richard West started to design the complex archiving system necessary to hold the data and to build up lightcurves that could be searched for planet transits. At this time the Open University also secured funding and joined the project, funding an additional camera on SuperWASP.

In 2003 Keele University joined the project, when Coel Hellier obtained £400k of SRIF2 funding, sufficient to build a copy of SuperWASP for the Southern Hemisphere. WASP-South would be sited at Sutherland in South Africa. Meanwhile, St. Andrews obtained further funding to enable SuperWASP-North and WASP-South to carry eight cameras each.

SuperWASP-North operated for 8 months in 2004, with 5 cameras and an observer continually present. It then closed for an overhaul in 2005. Both SuperWASP-North and the newly built WASP-South opened for observing in early 2006, with 8 cameras each, and now as fully robotic observatories operated over the internet.

The first planets, WASP-1b and WASP-2b, came from SuperWASP-North’s 2004 observations. They were proven to be planets by radial-velocity followup observations at the Observatoire de Haute-Provence. The 2007 paper announcing them was led by Andrew Collier-Cameron. WASP-3, also from the 2004 data, was announced in 2007, in a paper led by Don Pollacco.

Meanwhile WASP-South candidates were being followed up by the University of Geneva using their CORALIE spectrograph on the Swiss/Euler telescope at La Silla. The first two WASP-South planets, WASP-4b and WASP-5b were announced in 2007 in papers led by David Wilson and David Anderson, two Keele PhD students who had done much to get WASP-South operating and to process the data.

Coel Hellier wrote a press release on WASP-3b, WASP-4b and WASP-5b, which resulted in their discovery being hailed by CNN and Time Magazine as among the Top Ten Scientific Discoveries of 2007. As a result of that, in the 2009 Romanes Lecture in Oxford, on British Science policy, then Prime Minister Gordon Brown described “British scientists … identifying three new planets outside our own solar system” as an example of “British scientists … continuously breaking new ground”.

In 2010 the WASP Consortium were awarded the Group Achievement Award by the Royal Astronomical Society. Since then they have gone on to become the world’s leading ground-based transit-search team, finding more transiting exoplanets than any other ground-based project. Only NASA’s Kepler space mission, costing 100 times as much, has found more.

Significant changes to the project came in 2013, with the move of (now) Professor Don Pollacco to Warwick University, as part of the development of his Next Generation Transit Search. The move of Richard West to Warwick also meant the WASP data centre moving from Leicester to Warwick.

By 2013 WASP planets totalled over 100, and the announcement of WASP-100b pushed the world-wide tally of known exoplanets over 1000. Meanwhile both WASP camera arrays continue to operate and the planet search continues apace.