Here’s another catch-up on a recent press release from MPIA, reporting on Hubble Space Telescope observations of WASP-121b.

“A group of astronomers, led by Thomas Mikal-Evans from the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy, have made the first detailed measurement of atmospheric nightside conditions of a tidally locked hot Jupiter. By including measurements from the dayside hemisphere, they determined how water changes physical states when moving between the hemispheres of the exoplanet WASP-121 b. While airborne metals and minerals evaporate on the hot dayside, the cooler night side features metal clouds and rain made of liquid gems. This study, published in Nature Astronomy, is a big step in deciphering the global cycles of matter and energy in the atmospheres of exoplanets.”

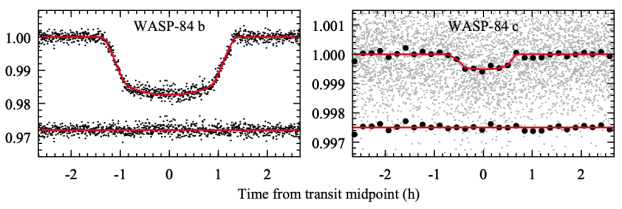

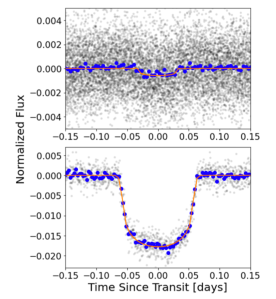

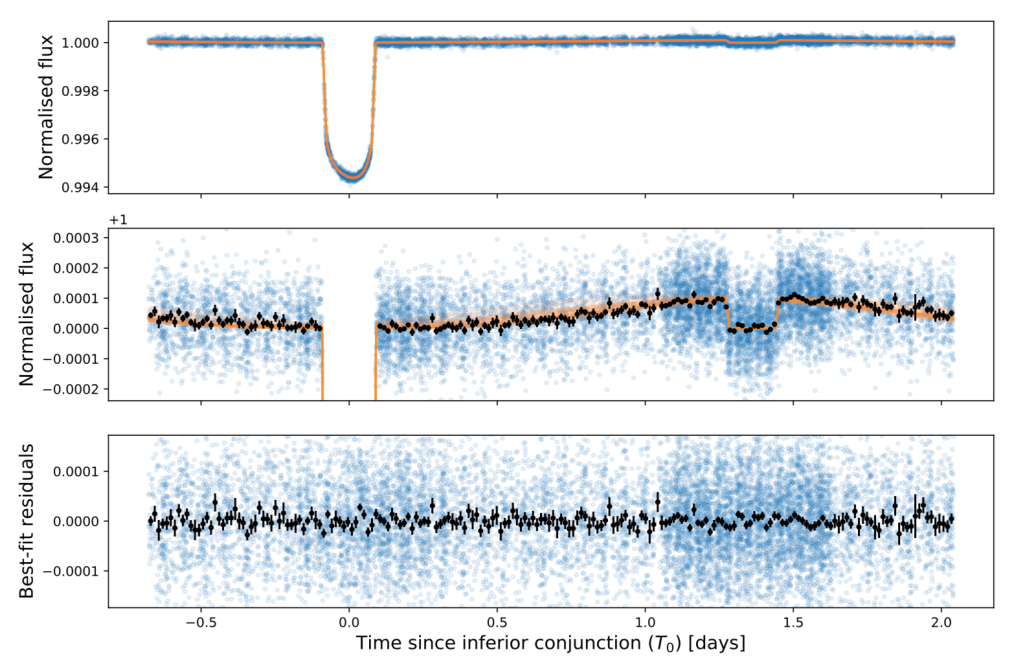

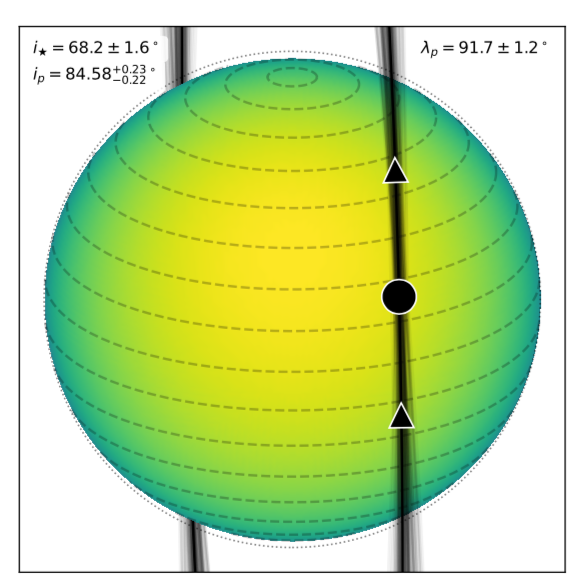

“To probe the entire surface of WASP-121 b, we took spectra with Hubble during two complete planet revolutions,” co-author David Sing from the Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, USA, explains. With this technique and supported by modelling the data, the group probed the upper atmosphere of WASP-121 b across the entire planet and, in doing so, observed the complete water cycle of an exoplanet for the first time.

“On the side of the planet facing the central star, the upper atmosphere becomes as hot as about 3000 degrees Celsius. At such temperatures, the water begins to glow, and many of the molecules even break down into their atomic components. The Hubble data also reveal that the temperature drops by approximately 1500 degrees Celsius on the nightside hemisphere. This extreme temperature difference between the two hemispheres gives rise to strong winds that sweep around the entire planet from west to east, dragging the disrupted water molecules along. Eventually, they reach the nightside. The lower temperatures allow the hydrogen and oxygen atoms to recombine, forming water vapour again before being blown back around to the dayside and the cycle repeats. Temperatures never drop low enough for water clouds to form throughout the cycle, let alone rain.”

“Instead of water, clouds on WASP-121 b mainly consist of metals such as iron, magnesium, chromium and vanadium. Previous observations have revealed the spectral signals of these metals as gases on the hot dayside. The new Hubble data indicate that temperatures drop low enough for the metals to condense into clouds on the nightside. The same eastward flowing winds that carry the water vapour across the nightside would also blow these metal clouds back around to the dayside, where they again evaporate.

“Strangely, aluminium and titanium were not among the gases detected in the atmosphere of WASP-121 b. A likely explanation for this is that these metals have condensed and rained down into deeper layers of the atmosphere, not accessible to observations. This rain would be unlike any known in the Solar System. For instance, aluminium condenses with oxygen to form the compound corundum. With impurities of chromium, iron, titanium or vanadium, we know it as ruby or sapphire. Liquid gems could therefore be raining on the nightside hemisphere of WASP-121 b.”

The press release has been taken up by numerous media and press websites.