A team using NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope has detected water in the atmosphere of five exoplanets. Three of these are WASP planets, WASP-12b, WASP-17b and WASP-19b. They were chosen because they orbit relatively bright stars and because they are close-in “hot Jupiter” planets with bloated and puffed-up atmospheres, the best targets for the highly demanding task of discerning molecules in those atmospheres. This study demonstrates how valuable WASP planets are for exoplanet research.

An artist’s conception of WASP-12b, a hot-Jupiter planet orbiting so closely that its atmosphere is blasted by irradiation from its star

The NASA press release has been reported by websites and newspapers worldwide. It reads:

Hubble Traces Subtle Signals of Water on Hazy Worlds Dec. 3, 2013

Using the powerful eye of NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope, two teams of scientists have found faint signatures of water in the atmospheres of five distant planets.

The presence of atmospheric water was reported previously on a few exoplanets orbiting stars beyond our solar system, but this is the first study to conclusively measure and compare the profiles and intensities of these signatures on multiple worlds.

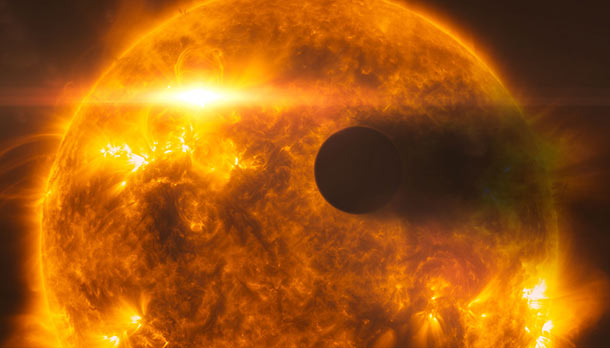

The five planets — WASP-17b, HD209458b, WASP-12b, WASP-19b and XO-1b — orbit nearby stars. The strengths of their water signatures varied. WASP-17b, a planet with an especially puffed-up atmosphere, and HD209458b had the strongest signals. The signatures for the other three planets, WASP-12b, WASP-19b and XO-1b, also are consistent with water.

“We’re very confident that we see a water signature for multiple planets,” said Avi Mandell, a planetary scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md., and lead author of an Astrophysical Journal paper, published today, describing the findings for WASP-12b, WASP-17b and WASP-19b. “This work really opens the door for comparing how much water is present in atmospheres on different kinds of exoplanets, for example hotter versus cooler ones.”

The studies were part of a census of exoplanet atmospheres led by L. Drake Deming of the University of Maryland in College Park. Both teams used Hubble’s Wide Field Camera 3 to explore the details of absorption of light through the planets’ atmospheres. The observations were made in a range of infrared wavelengths where the water signature, if present, would appear. The teams compared the shapes and intensities of the absorption profiles, and the consistency of the signatures gave them confidence they saw water. The observations demonstrate Hubble’s continuing exemplary performance in exoplanet research.

“To actually detect the atmosphere of an exoplanet is extraordinarily difficult. But we were able to pull out a very clear signal, and it is water,” said Deming, whose team reported results for HD209458b and XO-1b in a Sept. 10 paper in the same journal. Deming’s team employed a new technique with longer exposure times, which increased the sensitivity of their measurements.

The water signals were all less pronounced than expected, and the scientists suspect this is because a layer of haze or dust blankets each of the five planets. This haze can reduce the intensity of all signals from the atmosphere in the same way fog can make colors in a photograph appear muted. At the same time, haze alters the profiles of water signals and other important molecules in a distinctive way.

The five planets are hot Jupiters, massive worlds that orbit close to their host stars. The researchers were initially surprised that all five appeared to be hazy. But Deming and Mandell noted that other researchers are finding evidence of haze around exoplanets.

“These studies, combined with other Hubble observations, are showing us that there are a surprisingly large number of systems for which the signal of water is either attenuated or completely absent,” said Heather Knutson of the California Institute of Technology, a co-author on Deming’s paper. “This suggests that cloudy or hazy atmospheres may in fact be rather common for hot Jupiters.”Hubble’s high-performance Wide Field Camera 3 is one of few capable of peering into the atmospheres of exoplanets many trillions of miles away. These exceptionally challenging studies can be done only if the planets are spotted while they are passing in front of their stars. Researchers can identify the gases in a planet’s atmosphere by determining which wavelengths of the star’s light are transmitted and which are partially absorbed.